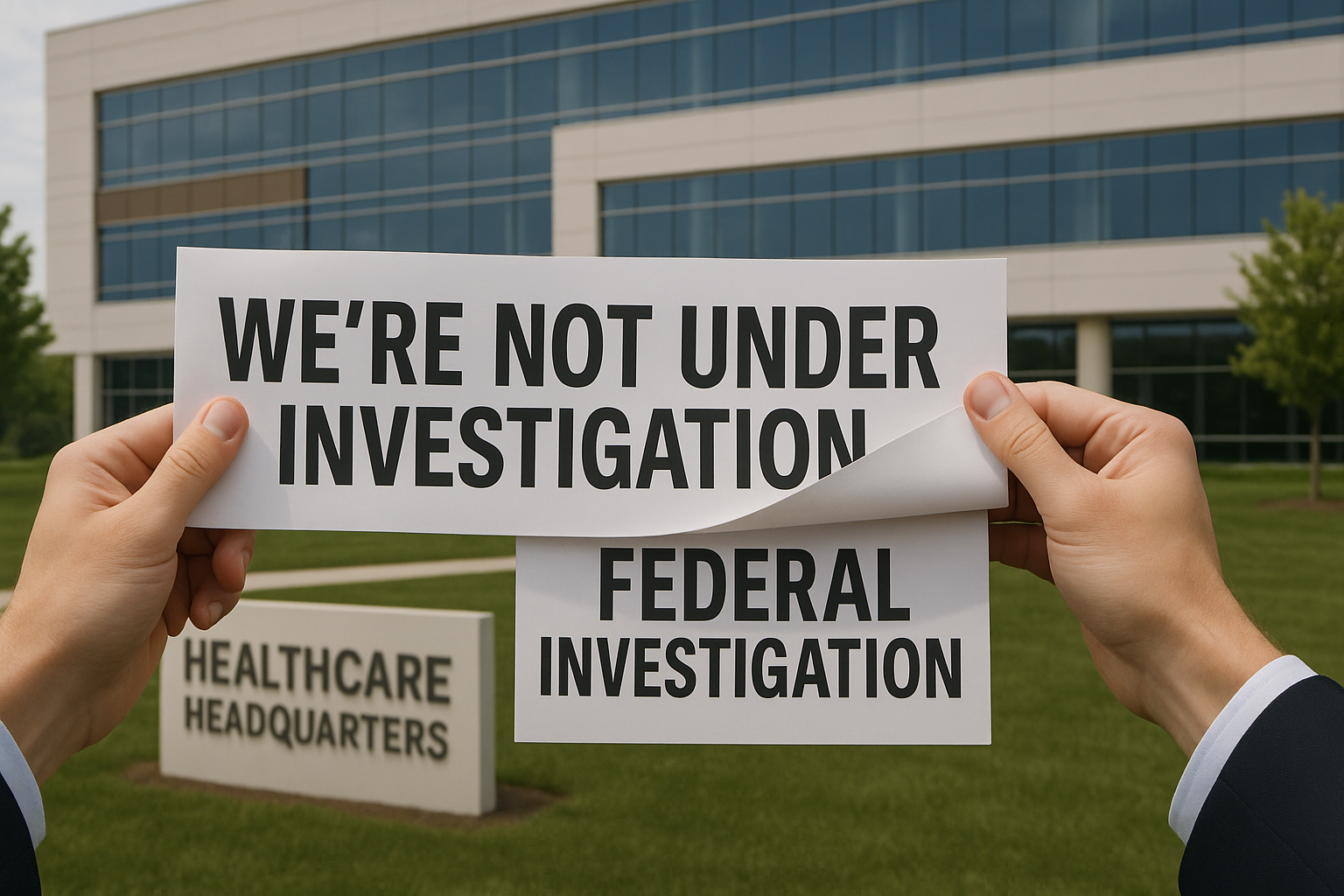

In the annals of corporate communications, few maneuvers are as classic as the "we have no idea what you're talking about" followed by the "oh, that federal investigation" pivot. UnitedHealth Group has now executed this move with textbook precision.

Two months after emphatically dismissing a Wall Street Journal report about a federal investigation as "deeply irresponsible" journalism, UnitedHealth has quietly acknowledged that—surprise!—it is indeed under federal investigation. The healthcare giant admitted in a regulatory filing Monday that the Justice Department is investigating its Medicare Advantage billing practices.

Let's rewind the tape. Back in May, when the WSJ first reported on potential federal scrutiny, UnitedHealth responded with the corporate equivalent of indignation: "We are not aware of being under investigation by the DOJ related to our Medicare Advantage business, and have no understanding of what allegations might be at issue." The company called the reporting "deeply irresponsible" for good measure.

What makes this particularly amusing is that in the same May statement, UnitedHealth curiously felt compelled to mention the "integrity of our Medicare Advantage plans"—despite supposedly having no clue what the investigation might be about. It's rather like telling the police "I definitely wasn't anywhere near the bank that was robbed" when they've only stopped you for a broken taillight.

The healthcare industry's relationship with Medicare Advantage has always been fascinating from a game theory perspective. The program allows private insurers to offer Medicare plans, with payment rates adjusted based on patient risk scores. The higher the risk score, the more money the insurer receives—creating what economists politely call "incentive alignment challenges."

A model I often use to understand these situations is the "selective disclosure equilibrium." In this model, companies reveal information based on a complex calculation involving legal requirements, reputational risk, and the probability of the information becoming public anyway. The optimal strategy often involves denying problematic information until the moment when acknowledging it becomes less costly than continued denial.

UnitedHealth is hardly the first company to follow this playbook. Facebook (now Meta) spent years dismissing concerns about its data practices before Cambridge Analytica forced a reckoning. Boeing insisted its 737 MAX planes were safe until the evidence became impossible to ignore. Wells Fargo initially downplayed its fake accounts scandal as the work of a few bad apples.

The healthcare giant's disclosure comes amid broader scrutiny of Medicare Advantage billing practices across the industry. Humana, CVS Health's Aetna, and Elevance Health have all faced similar questions. The Justice Department has been particularly interested in "upcoding"—the practice of making patients appear sicker on paper than they are in reality.

What's particularly interesting here is the timing. UnitedHealth chose to acknowledge the investigation in a quarterly regulatory filing—a classic "take out the trash" approach to bad news. Monday afternoon in July? Perfect time to bury information you'd rather not have spotlighted.

From an investor perspective, the financial markets seem to have mostly shrugged off the news. UnitedHealth's stock dipped slightly but remains near all-time highs. This reflects what I call the "priced-in presumption"—the notion that sophisticated investors already assumed something fishy was happening despite official denials.

The situation raises interesting questions about corporate credibility. What's the value of a company's public statements if they can be so dramatically contradicted just weeks later? How should we weigh management's vehement denials against industry patterns and journalistic investigations?

I'm reminded of a conversation I once had with a corporate communications executive who told me, "In crisis communications, our first job is to buy time." Perhaps UnitedHealth was simply following this maxim, hoping the story would fade or that the investigation would quietly resolve.

The irony here is that by calling the WSJ's reporting "deeply irresponsible," UnitedHealth created a much more embarrassing situation for itself. Had it simply issued a generic "we don't comment on rumors" statement, today's revelation would be far less noteworthy.

For investors, regulators, and journalists, the lesson is clear: When a company specifically denies knowledge of an investigation while simultaneously defending itself against the alleged focus of that investigation, it might be worth taking that denial with a warehouse of salt.

Everything is securities fraud? Not quite. But selective memory about federal investigations certainly makes for interesting securities filings.