The stock market is throwing one hell of a party right now. But like any good rager, someone's gonna have to clean up the mess when it's over—and from where I'm sitting, that cleanup could be brutal.

Look, we all know that famous Keynes line about markets staying irrational longer than you can stay solvent. It's the investor's favorite security blanket when things get weird. But what everyone conveniently forgets is the inevitable second act: reality always—always—catches up.

Main Street is feeling it already. I've spoken with dozens of small business owners over the past month who describe the tariff situation as "economic whiplash." One week they're scrambling to rework their entire supply chain around a new 10% tariff, the next they're told "nevermind!" as policy reverses faster than a politician caught on hot mic.

Big corporations? They'll manage. They always do. But the local shops operating on razor-thin margins? For them, this isn't just annoying—it's existential.

And here's something that keeps me up at night: small businesses employ nearly half of America's private workforce. When they start going under (not if, when), unemployment doesn't creep up in those neat little quarter-point increments economists love to graph. It spikes. Hard.

The valuation picture is... well, bonkers is the technical term I believe.

The S&P is currently rocking a P/E ratio above 28. For those who don't speak market-ese, that's not just expensive—it's "I'll take that Manhattan penthouse with the helicopter pad and gold-plated toilets" expensive. Historically, whenever markets stretch beyond 25, things eventually snap back with all the gentleness of a bungee cord at maximum extension.

(Having covered three major market corrections since 2001, I've seen this movie before. The ending rarely changes.)

What we're witnessing reminds me of something an old hedge fund manager told me back in '99, while nursing his third scotch at a Wall Street bar that no longer exists. "Markets," he said, tapping his glass for emphasis, "can float on bullshit and dreams for a surprisingly long time. But eventually, someone has to show the money."

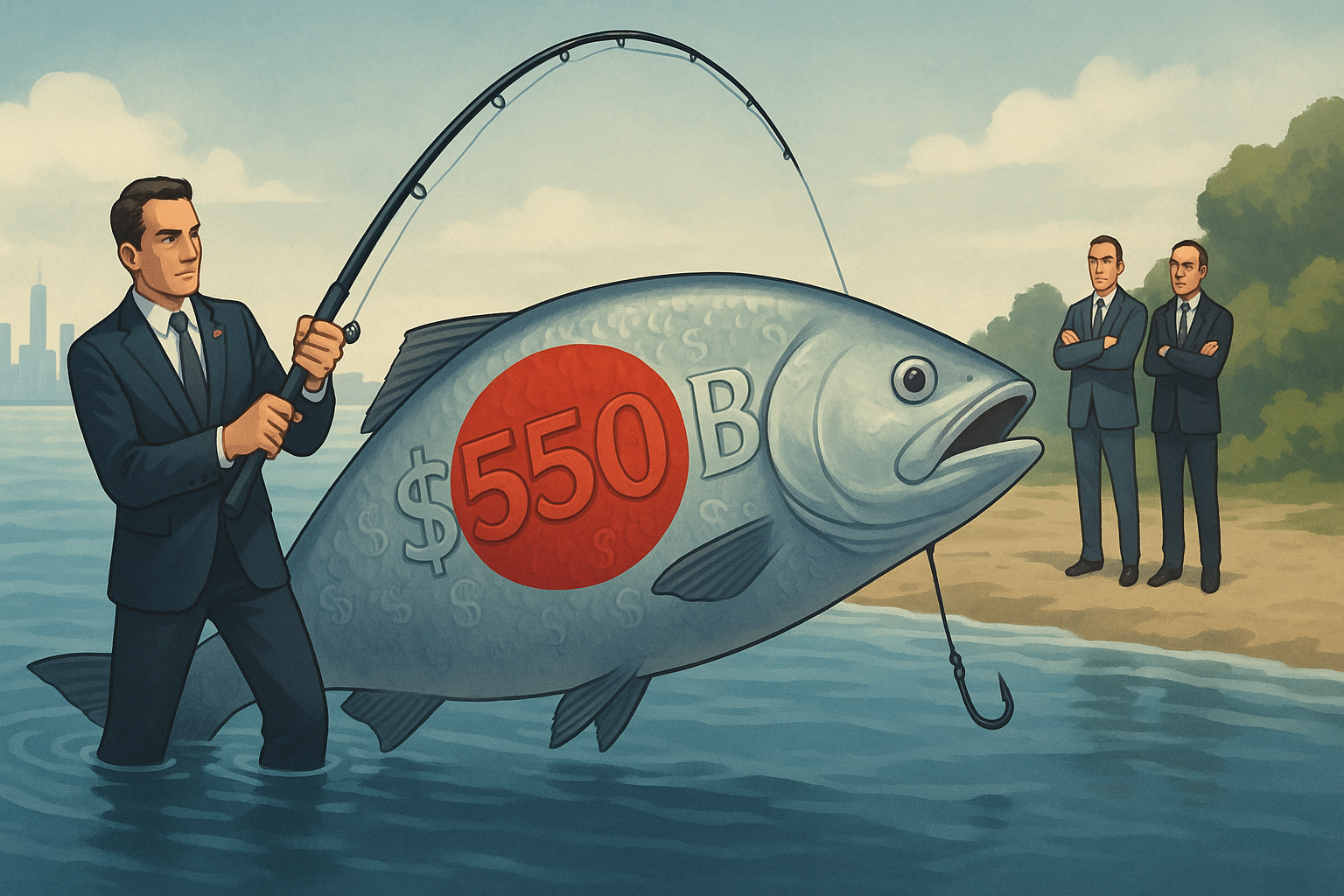

The Magnificent Seven tech stocks have been Atlas-ing this market skyward, but there's only so long seven companies—no matter how magnificent—can carry everything else.

Then there's the international angle. Foreign investors are looking at America with the kind of side-eye usually reserved for that friend who keeps changing the rules of Monopoly when they're losing. Bond auctions are getting weird, China's making economic moves that would've been unthinkable a decade ago, and the dollar... well, it's taking shots from all sides.

And now we're talking about this new equities tax? The so-called "Big Beautiful Bill"? In the global competition for investment capital, this is basically America saying, "Hey, maybe try investing somewhere else?" Bold strategy, Cotton.

This isn't meant to be some doom-and-gloom prophecy. The big tech companies are still making money hand over fist. Their guidance isn't terrible.

But earnings—even spectacular ones—can only fight gravity for so long when everything else turns south. Even Michael Phelps would eventually tire swimming against a tsunami.

The gap between economic reality and market fantasy has been widening for so damn long that investors have just... accepted it? Like this is normal? History suggests there's no such thing as a permanent "new normal" in markets—just temporary mass delusions waiting for their appointment with reality.

So while I'm not suggesting you liquidate everything and build a bunker filled with gold bars and canned beans (though I know a guy who has), maybe—just maybe—a little caution wouldn't be the worst idea right now.

Because when reality finally crashes this party, it won't be knocking politely before entering. It'll kick the door down.