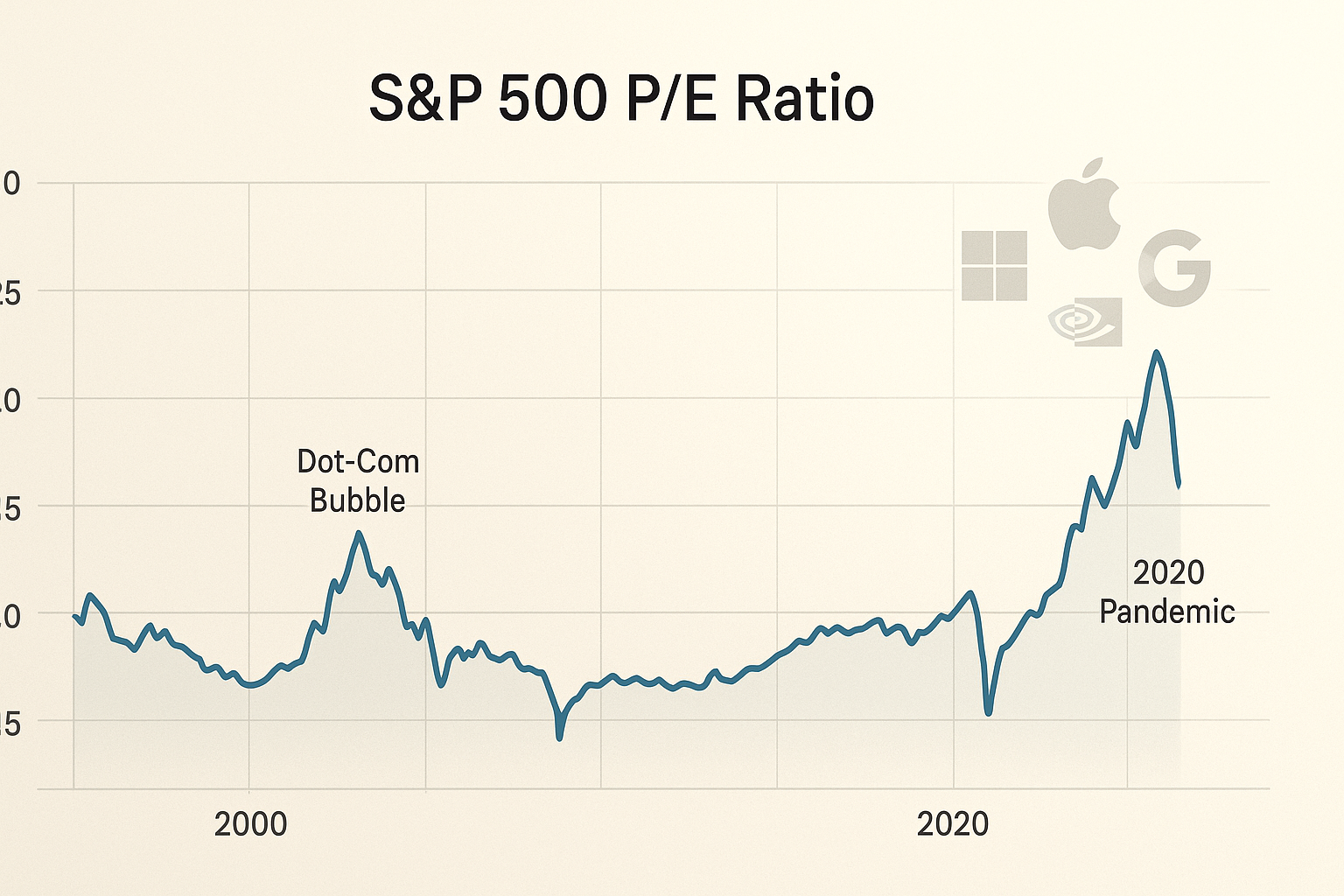

The S&P 500's price-to-earnings ratio is creeping toward 30, a level that should make any seasoned market watcher at least raise an eyebrow. We haven't seen these valuations since the dot-com bubble—well, except for that weird pandemic blip when earnings temporarily collapsed, but that was an accounting anomaly more than a true valuation signal.

What's particularly unsettling about today's situation is that it's happening against a backdrop of record corporate profits and economic growth. This ain't your typical bubble scenario.

I've been tracking these numbers for years now, watching with a mixture of professional curiosity and personal dread as the metrics climb ever higher. Remember when a PE of 15 was considered "fair value" for the market? Those days feel as distant as three-martini lunches and smoking in the office.

The market skeptics—and lord knows there are plenty—insist we're witnessing Bubble 2.0. But then again, these same voices have predicted approximately 37 market crashes since Obama's first term, so their credibility is... let's just say it's seen better days.

Look, we need to consider what's actually changed about the index itself. Today's S&P 500 is essentially a technology index with some other stuff thrown in for old times' sake. When Apple, Microsoft, Nvidia, Amazon, and Google make up such a massive chunk of the market cap, traditional valuation metrics start to lose some meaning.

These aren't your grandfather's blue chips. These are companies that can scale globally with minimal capital investment, sporting profit margins that would make a 1980s industrialist weep with envy. Microsoft casually generates 40% operating margins while traditional manufacturers might kill for 15%. Different animals entirely.

So maybe—just maybe—comparing today's PE ratios to historical averages is like comparing Netflix to Blockbuster. The business models have fundamentally changed.

That said (and this is important), I'm not completely comfortable waving away valuation concerns with the "it's different this time" magic wand. That particular phrase has preceded some of history's most spectacular financial face-plants.

What fascinates me about this market is the extreme concentration of these valuations. Strip out the top 10 companies, and suddenly the remaining 490 look much less bubbly. This two-tiered market creates its own peculiar risks—if the generals start retreating, who's left to lead the charge?

Interest rates complicate the picture further. Despite Powell's best efforts, rates remain historically low in real terms. The equity risk premium—that extra return you demand for the privilege of riding the stock market rollercoaster instead of parking cash in Treasury bills—has compressed to levels that would have seemed absurd twenty years ago.

There's a certain logic to this in our TINA economy ("There Is No Alternative," for those who've somehow avoided this particularly annoying Wall Street acronym). When bonds yield peanuts, investors will naturally accept lower compensation for stock market risk.

But here's where I start getting nervous. Current valuations seem to be pricing in a future where everything—and I mean everything—goes perfectly. Continued earnings growth? Check. Multiple expansion? Sure, why not! Soft landing? Of course! Sustained profit margins at historical highs? Absolutely!

C'mon now. When has everything ever gone according to plan?

I'm reminded of something Jeremy Grantham observed about institutional investor behavior. Fund managers rarely get fired for losing money when everyone else is losing money too. But they absolutely get shown the door for missing out on a bull market. This creates powerful herding instincts that can drive markets to irrational extremes.

For my money (quite literally—I've got skin in this game), the most telling indicator is Shiller's CAPE ratio, which smooths out earnings over a 10-year period. It's currently around 35, a level only exceeded during the height of dot-com madness. Historically, elevated CAPE ratios have signaled lower future returns—not necessarily crashes, but extended periods of mediocre performance.

This doesn't mean you should liquidate your 401(k) tomorrow. Timing the market remains a fantastic way to underperform, and structural changes in business models might justify somewhat higher baseline valuations than historical norms.

But it probably does mean recalibrating return expectations. The next decade is unlikely to deliver the same generous results as the last.

As Buffett likes to say, "Be fearful when others are greedy." With PEs pushing 30, there's enough greed in the air to make a value investor's skin crawl. A healthy dose of caution might be the appropriate response to today's frothy market environment.

After all, gravity still exists. Even in the stock market.