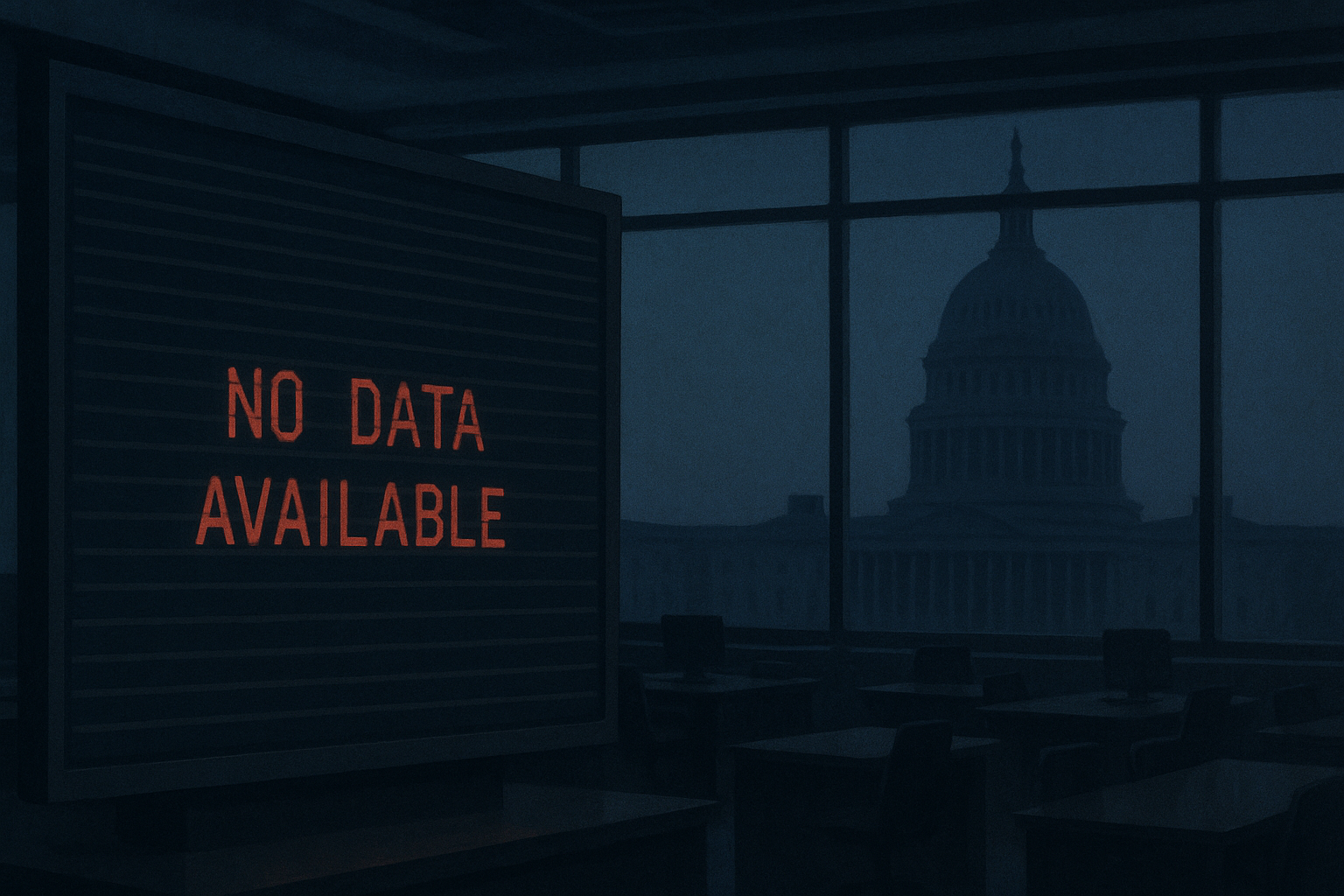

The Labor Department just dropped a bombshell that's somehow both entirely predictable and deeply unsettling: if the government shuts down, America's economic data pipeline goes dark. Not partially dark. Not dimmed. Completely dark.

We're talking about the jobs report—that monthly ritual where economists, investors, and policymakers collectively hold their breath as numbers flash across screens, triggering billions in market movements. Gone. Vanished. At least until Congress remembers that funding the government is literally their job.

Having covered economic data releases for years, I can tell you there's nothing quite like the electric tension in a pressroom right before these numbers drop. That tension is about to be replaced with... nothing. A void. And markets absolutely hate voids.

"Information vacuums create volatility," a chief economist at a major Wall Street firm told me yesterday. "When reliable data disappears, people make decisions based on rumors and hunches instead. That rarely ends well."

The timing couldn't be worse. The Fed just cut rates for the first time in this cycle and is trying to navigate what might be the most delicate economic landing since, well, the last time they tried this. Now Jerome Powell and company might have to fly completely blind.

Look, there's something darkly comical about a government that can't agree on its own funding also failing to tell us whether its economy is growing, shrinking, or doing whatever economies do when nobody's watching. It's like a doctor refusing to give you your test results because the hospital billing department is having an argument.

The Labor Department's 73-page contingency plan (I read it so you don't have to) states with bureaucratic precision that "BLS will suspend all operations." That's government-speak for "the data factory is closed until further notice."

This creates a fascinating—if terrifying—natural experiment. What happens when markets accustomed to regular data feedings suddenly go cold turkey? We're about to find out, and I suspect it won't be pretty.

There's another angle here that isn't getting enough attention. This data blackout gives extraordinary advantage to those with alternative information sources. The playing field, never exactly level, tilts even further toward sophisticated players with proprietary data collections. The big banks and hedge funds? They'll manage. Small investors relying on government reports? Not so much.

I spoke with three former BLS statisticians who all expressed the same concern: once you interrupt the data collection process, you can't just flip it back on when funding returns. There are methodological issues, sampling problems... the statistical machinery that produces these numbers is delicate.

The cruel irony is that this potential information drought comes during an era where we're all supposedly drowning in data. Yet these government reports—often criticized, occasionally revised, perpetually scrutinized—provide the shared reality that markets need to function efficiently.

Wall Street pretends to be cynical about government data until it disappears. Then panic sets in.

The economic calendar for next week now has asterisks where certainties used to be. The jobs report, scheduled for Friday? *Subject to government being functional.

One Fed official I spoke with (who, unsurprisingly, requested anonymity) put it bluntly: "We've dealt with shutdowns before, but the timing of this one creates unique challenges for monetary policy decisions."

Translation: They're worried. And they should be.

In the meantime, economists are scrambling to beef up alternative indicators—private payroll reports, credit card spending data, anything that might fill the information gap. But these are poor substitutes for the comprehensive view that government statistics provide.

It's worth remembering that economic data isn't just numbers for traders to react to. These reports help determine everything from cost-of-living adjustments for retirees to funding formulas for social programs. The ripple effects of this darkness will extend far beyond Wall Street.

For now, we wait—for Congress to act, for data to flow again, for some semblance of normalcy to return to our economic information ecosystem. Though "normal" feels increasingly like a quaint relic of a more functional era.

Maybe there's a certain twisted poetry in all this. A nation that can't agree on basic facts losing access to the very data that might ground us in a shared reality.

Or maybe it's just another unnecessary crisis manufactured by a political system that seems increasingly designed to create them.

Either way, prepare for turbulence. Markets hate uncertainty almost as much as nature abhors a vacuum. And we're about to have plenty of both.