PrimaLend Capital Partners has filed for bankruptcy protection. Don't feel bad if you're scratching your head wondering who they are—I only caught wind of this myself days after it happened, which tells you something about how financial news travels in certain corners of the market.

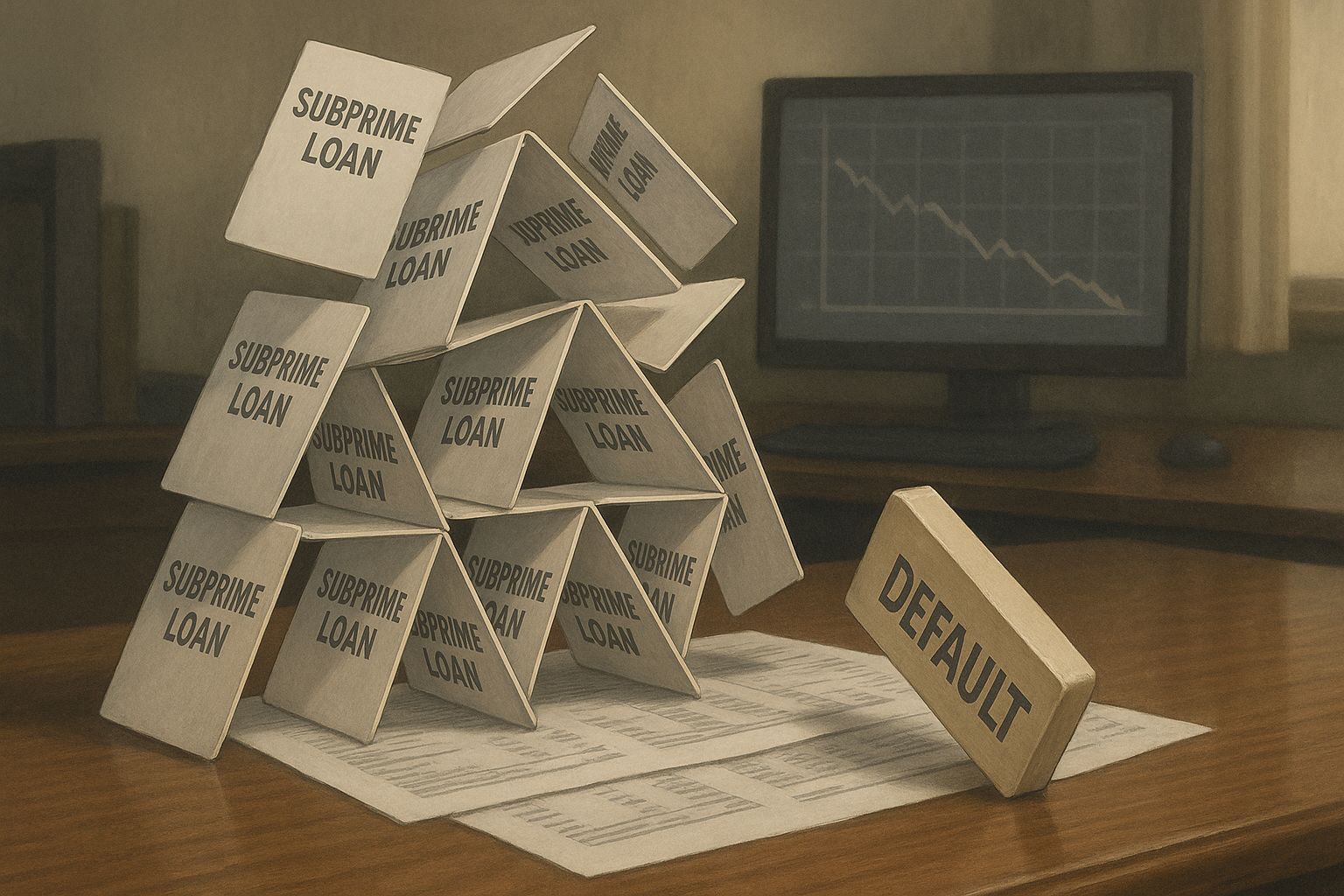

These subprime lending operations exist in a peculiar financial twilight zone. They're not quite prominent enough to make headlines when they implode, yet they matter enough to send ripples through specific segments of the credit markets. PrimaLend's collapse follows that well-worn path of subprime lenders who expand like crazy during good times, only to discover their business model has all the structural integrity of a house of cards in a wind tunnel.

Look, here's the fundamental contradiction at the heart of subprime lending: you're simultaneously betting that you can price risk accurately for borrowers that mainstream banks won't touch AND that those same borrowers will somehow defy the risk assessment that landed them in the subprime category to begin with. It's like thinking you've identified which specific ice cubes won't melt in hot water.

The whole scheme works beautifully... until suddenly it doesn't.

During boom times, defaults stay manageable, investors throw money at anything promising decent yield, and everyone pats themselves on the back for their brilliant risk models. Then the economic winds shift just slightly, defaults tick up a notch, and the math that made everything work collapses with breathtaking speed.

What's particularly fascinating about PrimaLend's demise is how long it took for anyone to notice. When JPMorgan sneezes, it's instant front-page news. When smaller players like PrimaLend go belly-up, there's often this information lag—a real-world demonstration of market inefficiency that creates pockets of opportunity (or danger, depending where you're standing).

I've seen this movie before, and the ending isn't pretty. During the 2008 meltdown, subprime lenders were dropping like flies months before the broader market acknowledged we had a serious problem. The canaries were already stiff in the coal mine, but everyone was too busy watching the Dow to notice.

So is PrimaLend just one badly managed company, or is it a warning sign of broader trouble brewing in consumer credit markets?

Hard to say for sure, but it's worth noting that consumer delinquencies have been creeping up across several loan categories. Credit card delinquencies hit 3.01% in the fourth quarter of last year—the highest since 2012. Auto loan delinquencies aren't looking too hot either.

The Fed's higher-for-longer rate policy puts particular strain on subprime lenders. They operate on razor-thin margins, and their customers have virtually no financial buffer to absorb higher borrowing costs. It's a bit like running a snowplow business in Miami—the fundamental conditions just don't support your business model.

One telling aspect of this bankruptcy is how quietly PrimaLend slipped beneath the waves. No dramatic headlines, no market panic, just a filing that most of us learned about after the fact. This suggests either the market has already priced in trouble among smaller subprime players, or—and this is what keeps me up at night—we're still in those early stages where isolated failures haven't yet formed a recognizable pattern.

For anyone with skin in the game, the million-dollar question is about contagion. Are PrimaLend's issues unique to them, or are they just the first visible cracks in a more systematically fragile structure? The answer probably hinges on how concentrated exposure to similar lenders is among larger financial institutions, and whether funding markets stay open to players in this space.

I remember talking with a credit trader back in '07 who told me, "The weird thing about credit markets is nothing happens until suddenly everything happens." That's exactly how these situations tend to develop—glacially slow, then all at once.

For now, PrimaLend's bankruptcy remains just a data point rather than a confirmed trend. But in financial markets, as in earthquake monitoring, sometimes a single tremor deserves our undivided attention. Might be nothing at all. Or might be the first warning shock of something bigger coming.

Either way, the delayed reaction to their collapse is itself information worth considering.