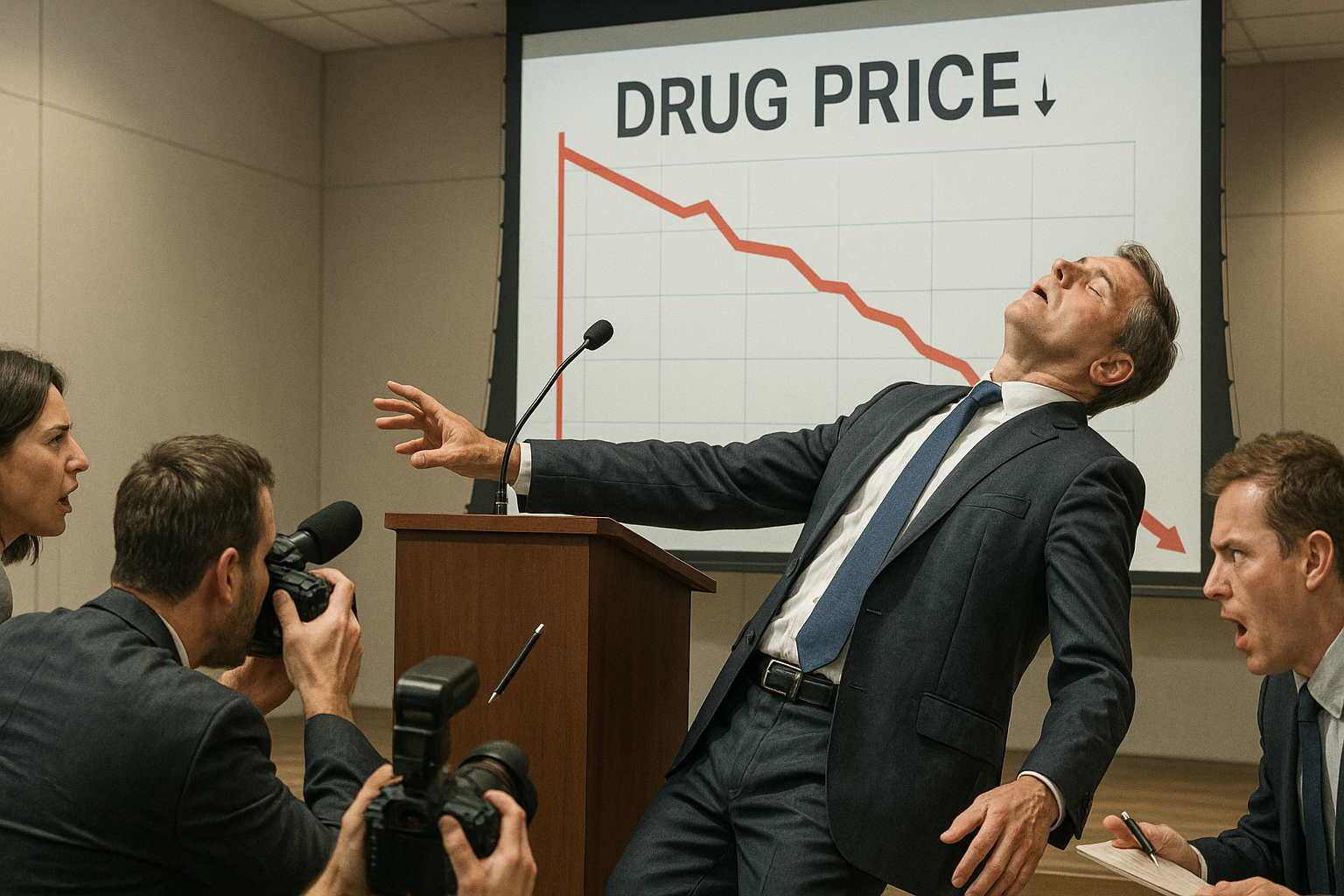

In a moment that political satirists could only dream of scripting, Novo Nordisk executive Gordon Findlay crumpled to the floor yesterday—directly behind President Trump and precisely as the commander-in-chief was touting his administration's success at lowering prescription drug prices.

Talk about timing.

I was watching the livestream when it happened, and the collective gasp from reporters was audible even through my mediocre laptop speakers. One moment, Trump was declaring victory over pharmaceutical pricing; the next, a pharmaceutical executive was literally collapsing under the apparent weight of this news.

Look, fainting happens. Low blood sugar, locked knees, overheating—there are dozens of perfectly innocent explanations. But sometimes the universe delivers symbolism so on-the-nose you can't help but marvel at it.

"It was like watching a visual metaphor come to life," one White House correspondent told me afterward, requesting anonymity to speak candidly. "I mean, c'mon."

The scene grew stranger when both Robert Kennedy Jr. and Dr. Oz reportedly exited the room just as Findlay's medical emergency began. Having covered political events for years, I've seen plenty of figures duck out of ceremonies early—usually for mundane scheduling reasons—but the timing here raised eyebrows among the press corps.

Pharmaceutical pricing has always been a strange beast in American capitalism. It's this weird amalgamation of patent protection, insurance bureaucracy, and emotional appeals about saving lives. Companies like Novo Nordisk—Findlay's employer—have mastered what economists might call "moral arbitrage," extracting premium prices at the intersection of medical necessity and proprietary research.

And boy, has it worked for them.

Novo's stock has practically doubled over the past year, riding the wave of their GLP-1 drugs Ozempic and Wegovy. These medications have transcended their origins as diabetes treatments to become the weight-loss phenomenon du jour among celebrities and ordinary Americans alike. Their business strategy appears brilliantly simple: create something everyone desperately wants, ensure limited supply, and watch the money roll in.

(I called Novo Nordisk for comment about Findlay's condition, but they hadn't responded by press time.)

What makes yesterday's fainting spell so deliciously ironic is how it accidentally reinforces every cynical narrative about the pharmaceutical industry's allergic reaction to price constraints. We've all joked that pharma executives probably break out in hives at the mention of Medicare negotiation, but to have one actually collapse during the announcement?

That's commitment to the bit.

The pharmaceutical pricing system has long resembled what game theorists might call a "multiple equilibria problem." There's the high-price/low-volume equilibrium that maximizes manufacturer profits versus the low-price/high-volume model that would benefit patients. Most markets naturally find balance between these forces, but pharmaceuticals exist in this strange regulatory twilight zone where normal market pressures don't fully apply.

I remember interviewing a pharmaceutical lobbyist back in 2019 who, after three scotches, admitted: "We're not afraid of competition. We're afraid of government. Competition we can handle—we just buy it and shut it down."

Let's be fair, though. The pharmaceutical industry does crucial work. The COVID vaccines, cancer treatments, and yes, even those wildly popular weight-loss drugs represent genuine innovation that improves and saves lives.

But the pricing? That's where things get dicey.

When an insulin manufacturer's representative faints during a price cut announcement, it's hard not to see it as an inadvertent piece of performance art illustrating the industry's discomfort with any move toward pricing transparency.

I wish Mr. Findlay a speedy recovery, naturally.

I also wish for a pharmaceutical pricing system that doesn't give anyone—executives or patients—reason to feel faint in the first place.