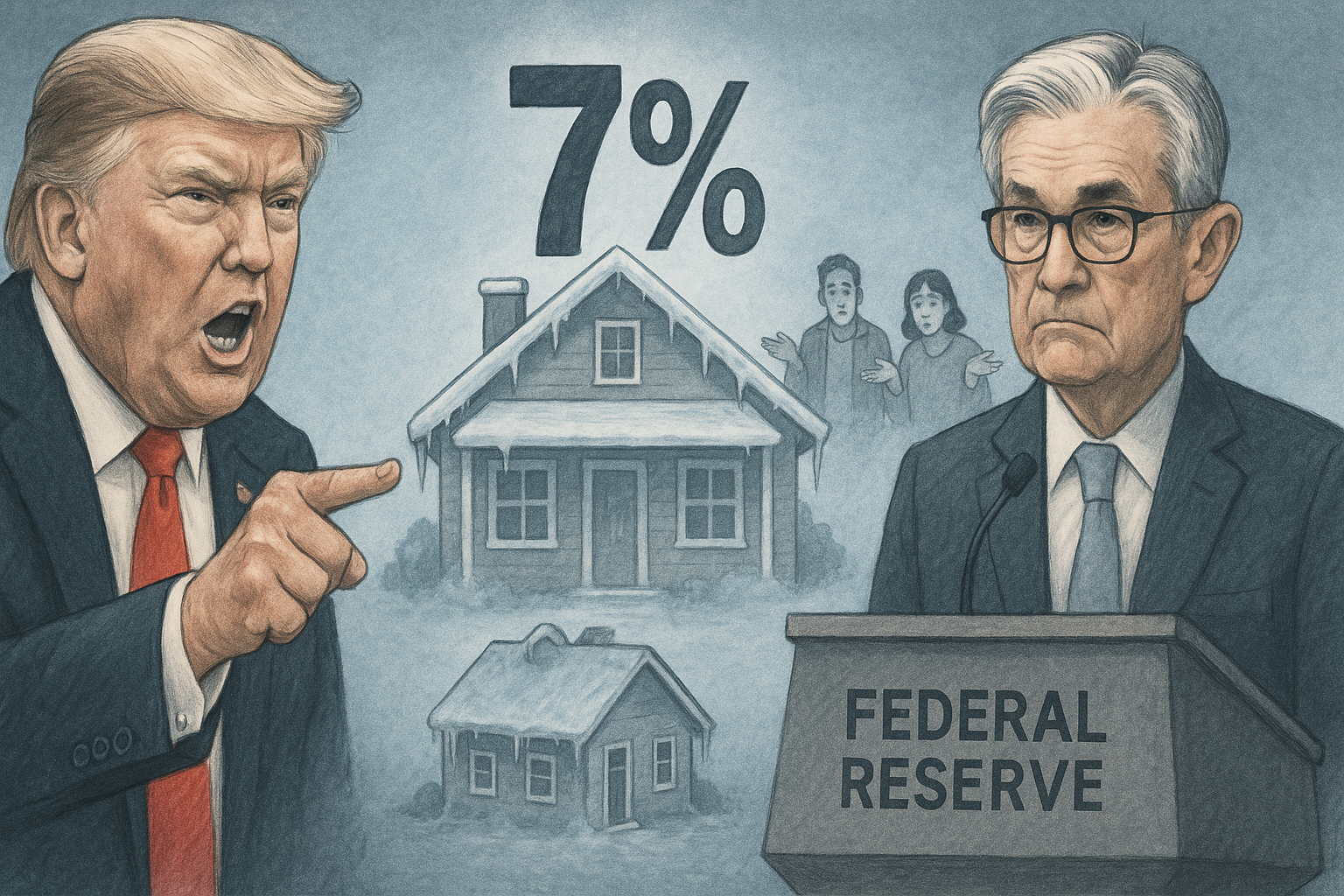

Donald Trump has found a new target for his infamous nicknaming strategy: Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, who's now been branded "Jerome 'Too Late' Powell" by the former president.

The attack—focused specifically on sky-high mortgage rates—comes as housing affordability has become a kitchen-table issue for millions of Americans. With rates hovering stubbornly around 7%, the housing market has essentially calcified, leaving both buyers and sellers stuck in an uncomfortable limbo.

Trump's timing is... well, let's just call it politically convenient. Politicians suddenly discovering monetary policy's importance about a year before voters head to the polls is a tale as old as central banking itself. It's the economic equivalent of claiming you've always been a huge fan of a band right when they hit the Billboard charts.

What makes this particular broadside interesting isn't just the catchy nickname. It's Trump's laser focus on mortgage rates rather than inflation generally.

The housing market is experiencing something economists call the "lock-in effect"—a phenomenon where homeowners with those sweet, sweet 3% pandemic-era mortgages would rather renovate their bathroom for the third time than voluntarily jump to a 7% loan. Can you blame them? I've talked to real estate agents who describe open houses where crickets literally have more presence than potential buyers.

"The market isn't just cool, it's cryogenically frozen," one Denver-based realtor told me last week.

Look, there's rich irony here that Trump conveniently overlooks. Powell—the very man he's now attacking—was his own appointee. This kind of selective amnesia is a classic example of what I like to call the "monetary policy ownership gradient." When the Fed's actions boost markets, politicians grab credit faster than free donuts disappear from a newsroom. When those same policies later cause pain? Suddenly the Fed is a rogue institution operating beyond anyone's control.

We've seen this movie before. Nixon's pressure on Arthur Burns in the '70s contributed to a decade of inflation nightmares. Paul Volcker later had to withstand enormous political heat to finally break inflation's back.

Powell finds himself in a particularly tricky spot. The Fed has only recently signaled a dovish turn, with potential rate cuts coming as early as September. Trump's criticism attempts to frame these upcoming cuts as embarrassingly overdue—a narrative that could stick regardless of when Powell actually pulls the trigger.

(Full disclosure: I've covered the Fed since 2018, and I've never seen the political pressure quite this explicit during an election cycle.)

What's particularly weird about the current housing situation is its contradictory nature. Transaction volumes have fallen off a cliff, yet prices in many markets keep climbing—a market that's simultaneously frozen AND overheated. That's not supposed to happen!

The question becomes: who exactly is Trump talking to here? Voters feeling the housing pinch? Powell himself? Or perhaps financial markets, which once moved dramatically based on his tweets?

Most financial professionals I've spoken with maintain healthy skepticism about political influence over monetary policy. Then again, they're equally concerned about rates staying too high for too long.

Powell, meanwhile, seems determined to stay above the political mud-wrestling match—a nearly impossible task when mortgage rates, inflation, and employment numbers will feature in basically every stump speech between now and November.

Seven percent mortgages in an election year. What could possibly go wrong?

For now, markets aren't reacting much to the political noise. Fed independence remains the consensus position among investors—at least officially. But Powell now faces the unenviable task of calibrating rate cuts in an environment where absolutely any move he makes will be viewed through a political lens.

The timing of the first cut, its size, the language accompanying it... all of it will be dissected for political implications.

And honestly? That's exactly how an election-year economy works. Always has been, probably always will be.