When Larry Fink talks inflation, Wall Street's collective ears perk up. BlackRock's chief recently declared inflation isn't just passing through—it's moving in and redecorating the place. Meanwhile, something else is happening that deserves just as much attention: the S&P 500 has morphed into what amounts to a tech fund with a side salad of... everything else.

I've been tracking market concentration trends since 2018, and let me tell you, we're in uncharted waters. The top 10 stocks now command more than 35% of the entire index. Thirty-five percent! That's not just concentration—that's practically a monopoly wearing a "diversified index" costume.

There's something deeply ironic about investors who simultaneously dump billions into S&P 500 funds while wringing their hands about market concentration. It's like complaining about climate change while idling your SUV.

So what exactly are you buying when you click "purchase" on that S&P 500 ETF?

The sales pitch hasn't changed: broad market exposure, sector diversification, a slice of American capitalism. That's the theory, anyway. The reality? You're essentially making a massive bet on a handful of tech giants with some economic confetti sprinkled on top.

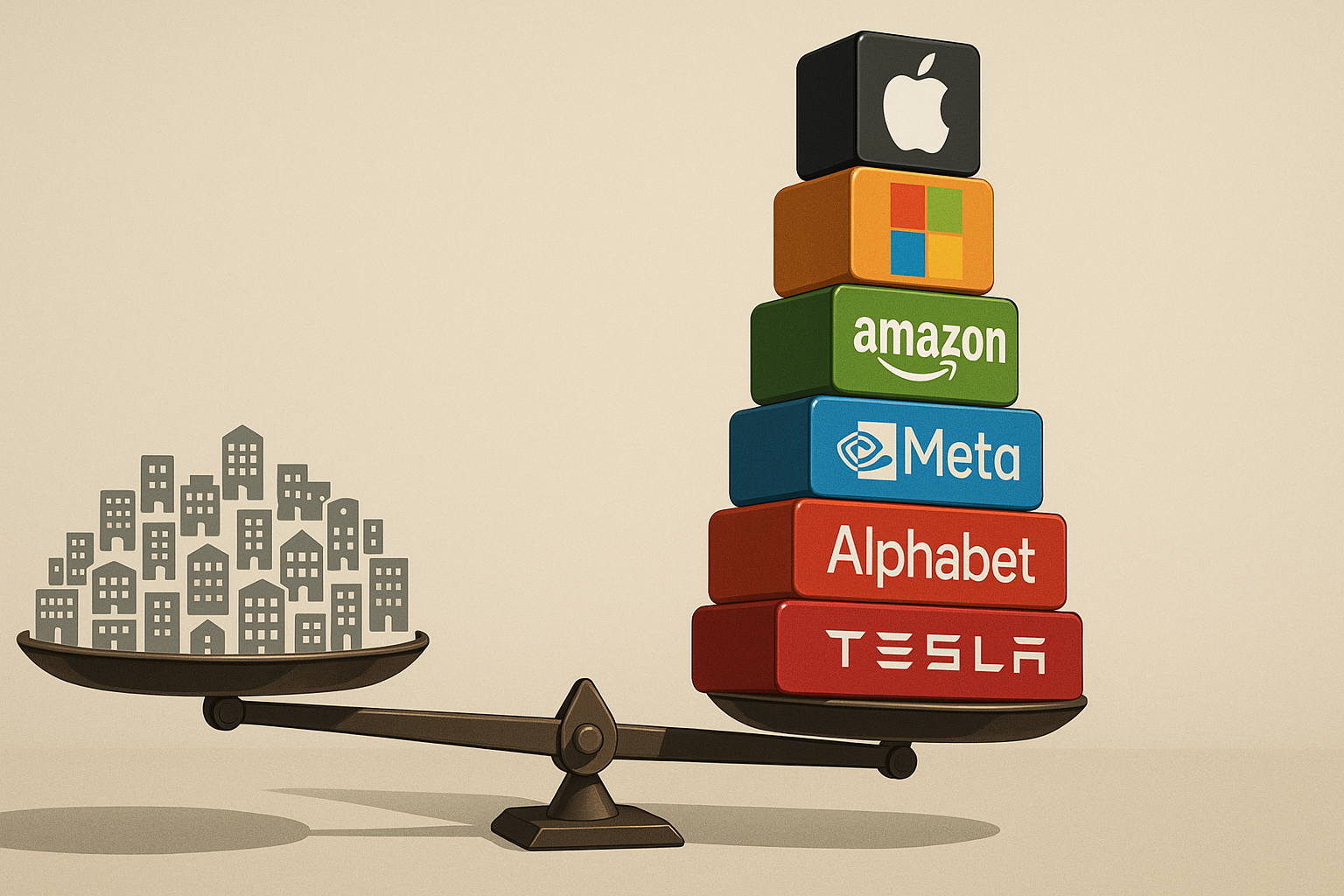

Look at it this way—Microsoft, Apple, Nvidia, Amazon, Meta, Alphabet, and Tesla now wield so much influence that they contribute more to index performance than hundreds of other companies combined. I checked the numbers myself last week, and it's staggering.

Think of today's S&P as a barbell where one end keeps getting heavier while the other end... doesn't. One side has the magnificent seven (plus a few friends), growing more massive by the quarter. The other side has hundreds of smaller companies whose collective relevance to your returns shrinks faster than a wool sweater in hot water.

This creates some weird distortions. The index can sport a seemingly reasonable P/E ratio around 21-22, while hiding extreme valuations underneath. (It's like saying you and Jeff Bezos have an average net worth of billions—technically true but utterly meaningless for your personal finances.)

For professional stock pickers, this concentration has been brutal. Missing just two or three of these mega-performers isn't just slightly underperforming—it's career suicide. Many fund managers I've spoken with describe it as the most challenging environment of their careers.

There are two ways to interpret what's happening:

Glass half full: These behemoths dominate because they genuinely create extraordinary value. Their outsized market caps reflect legitimate competitive advantages, superior business models, and exceptional growth potential, particularly as AI reshapes... well, everything.

Glass half empty (or maybe just realistic): We're caught in a self-reinforcing cycle where index inclusion drives flows, which drives performance, which increases index weight, which attracts more flows. Fundamentals matter, sure—but prices have entered their own reality.

Both perspectives contain nuggets of truth. These companies are exceptional businesses. But there's something circular happening with passive investing that's amplifying winner-take-all dynamics beyond what fundamentals alone would justify.

What fascinates me most is how this concentration warps market narratives. When a handful of tech giants determine whether your portfolio sinks or swims, everything becomes filtered through their lens. Interest rates rising? That's a tech story. Inflation worries? Tech story. Geopolitical tensions in the Middle East? Somehow, also a tech story.

Here's something that rarely gets mentioned in those glossy brochures: S&P 500 index investing isn't "passive" in any meaningful sense. When you buy an S&P fund, you're actively choosing to weight your investments exactly according to current market caps—essentially placing your biggest bets on whatever's already winning the race.

That's... a strategy, I guess? Not necessarily a bad one, but certainly not the neutral, judgment-free approach it's often portrayed as.

For investors who actually want diversification (you know, the thing everyone thinks they're getting), equal-weight S&P 500 funds present an interesting alternative. They've lagged cap-weighted indexes precisely because they don't go all-in on tech giants, but that same characteristic might prove valuable if—when?—market leadership eventually broadens or reverses.

Now, I'm not saying index investing is bad. For most people, it remains superior to expensive active management that typically underperforms. But understanding what you're actually buying matters. The S&P 500 of today bears little resemblance to the index of a decade ago.

The next time someone smugly tells you they're "just investing in the market," maybe ask them which market exactly. Because that S&P 500 fund is increasingly less a broad bet on American business and more a concentrated wager on a handful of tech giants with a garnish of diversification.

And hey, that might be exactly what you want! These companies have been extraordinary investments. Just know what you're buying—because it sure ain't your grandfather's index anymore.