I got an email last week that made me wince. You know the kind—where you can feel the family tension seeping through the screen.

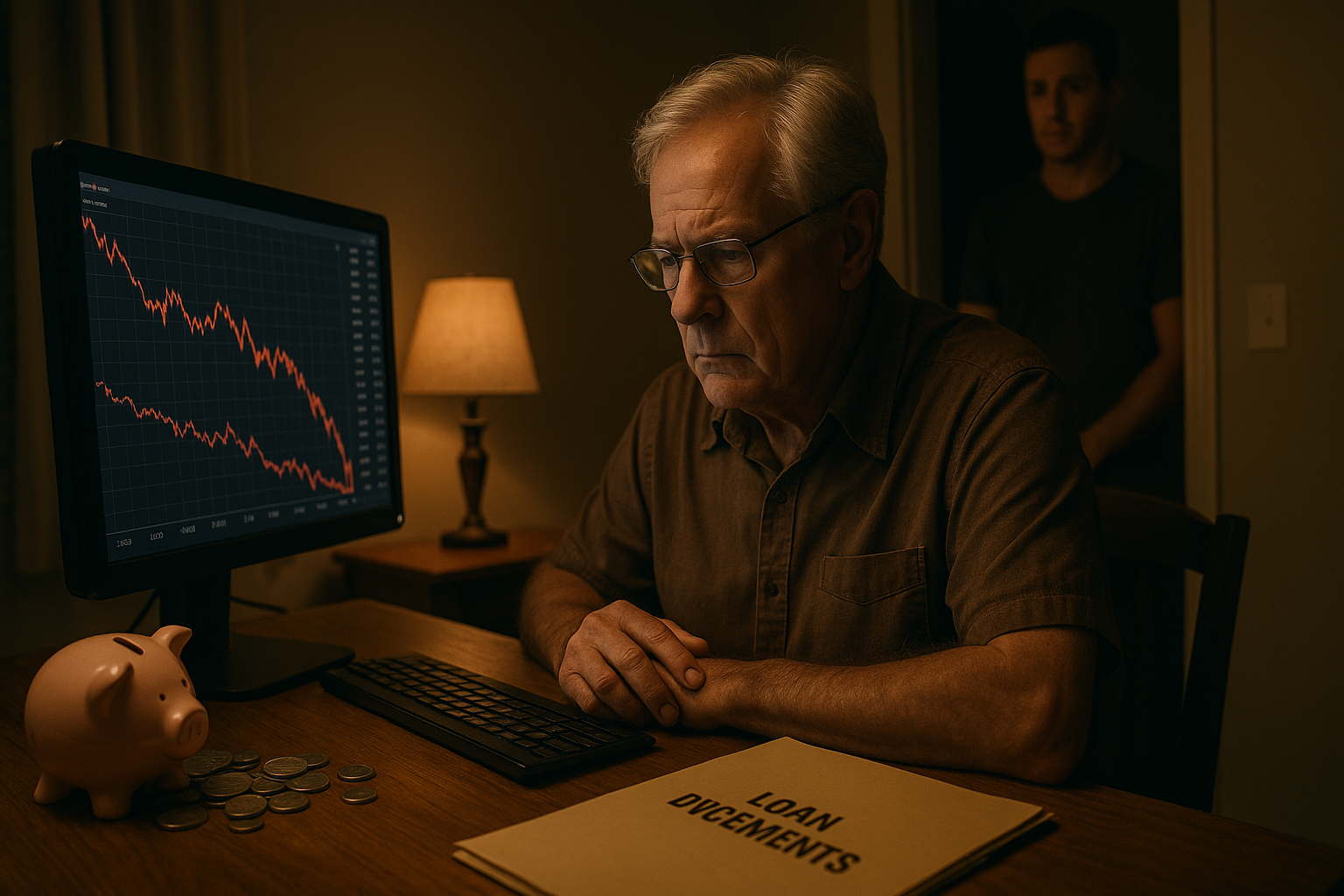

A concerned son wrote about his father—68 years old and supposedly enjoying retirement—who has apparently decided his golden years are the perfect time to transform himself into a day trader with a penchant for penny stocks and pharmaceutical longshots. It's like watching someone decide to take up tightrope walking at 70. Without the safety net.

The worst part? This isn't play money we're talking about. The father has taken out a multi-million dollar loan to finance his adventures in speculative investing. (Yes, you read that correctly. A loan. For millions. To buy penny stocks.)

Look, I've been covering personal finance for years, and this scenario plays out more often than you'd think. There's something about reaching retirement that makes some folks believe they've suddenly developed market-beating instincts that eluded them their entire working lives.

The father's portfolio reads like a cautionary tale in investment form. He's holding onto GoPro shares from 2015—a stock that's been in freefall since its IPO. Then there's Actinium Pharmaceuticals, down a staggering 90% after the FDA rejected their drug. And don't get me started on the high-fee mutual funds that are quietly siphoning away what little performance might have been salvaged.

Here's the brutal math that nobody wants to face: when a stock drops 90%—which happens distressingly often with speculative picks—it needs to grow by 900% just to get back to where you started. Nine hundred percent! Those aren't odds; they're fantasies.

The son, meanwhile, has taken a drastically different approach to investing. Index funds. A few carefully selected individual stocks. A modest crypto allocation (because, hey, it's 2023). It's the investment equivalent of eating your vegetables versus the father's all-candy diet.

This generational investment divide isn't unusual. I've interviewed dozens of financial advisors who describe similar patterns. Boomers who came of age during periods when markets were less efficient often maintain an almost religious devotion to stock picking. They reminisce about that one home-run stock from 1987 while conveniently forgetting the twenty strikeouts that followed.

But what do you do when someone you love is gambling away their financial security?

The psychology here is fascinating—and heartbreaking. Asking someone to admit their investment strategy is fundamentally flawed isn't just about money. It's asking them to reconsider part of their identity. That's why financial interventions often fail spectacularly.

I spoke with a financial therapist (yes, that's a real profession, and an increasingly necessary one) who suggested approaching situations like this by focusing first on concrete risks—like that massive loan—rather than trying to overhaul an entire investment philosophy overnight.

Another approach? Compromise. Perhaps Dad keeps 20% of his portfolio for his stock-picking adventures while moving the rest to safer waters. This preserves some sense of agency while dramatically reducing risk.

Sometimes, though... nothing works.

I remember interviewing a woman in Phoenix whose father lost his entire retirement trading options. "We had the interventions," she told me, voice cracking slightly. "We made the spreadsheets. We even got his longtime golf buddy—a retired financial advisor—to talk to him. Nothing stuck until the money was gone."

(That's the part of these stories that keeps me up at night.)

The most painful reality in financial journalism isn't reporting on market crashes or economic downturns. It's knowing that some readers will ignore every warning, every piece of evidence, every historical lesson—until it's too late.

There's wisdom in that old Wall Street saying about markets remaining irrational longer than you can remain solvent. But when it comes to family financial interventions, perhaps we need a new version: "A loved one can remain committed to bad investments longer than you can remain patient explaining why they're bad."

That's not just an investment truth. It's a human one.