Have you ever noticed how we treat trillion-dollar market caps like sporting milestones? The financial media erupts with the same breathless enthusiasm typically reserved for Olympic records whenever Apple or Microsoft adds another zero to their valuation. It's a bit ridiculous when you think about it.

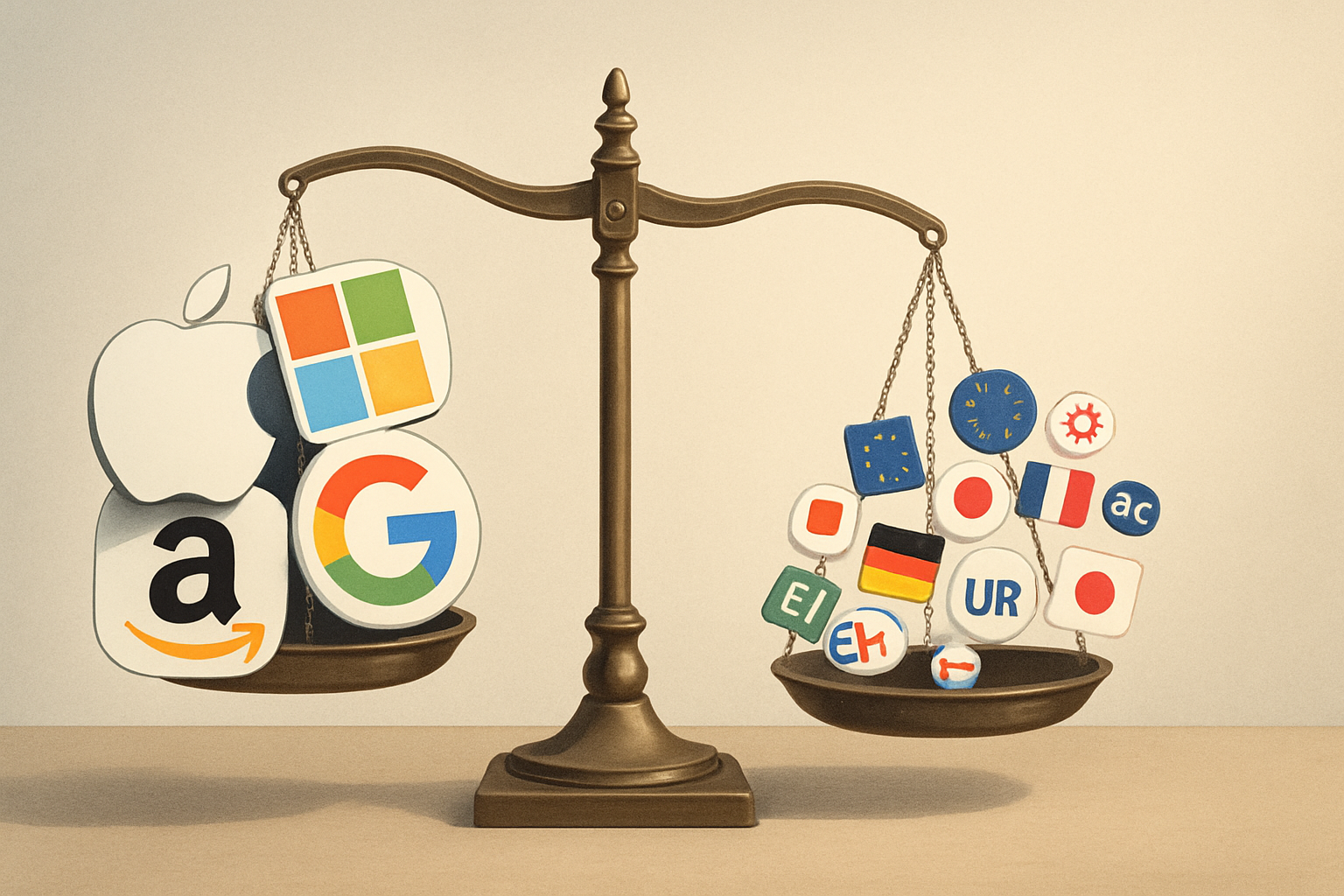

But here's the thing—this obsession with corporate behemoths isn't just financial entertainment. The growing dominance of mega-caps is reshaping investment landscapes in ways that matter deeply for everyday investors, especially when comparing U.S. markets to their international counterparts.

I've been tracking this divergence for years, and the numbers have become too stark to ignore.

The S&P 500—supposedly a diversified collection of America's leading businesses—now has roughly a third of its weight concentrated in just ten companies. Let that sink in. When you buy that index fund in your 401(k), one out of every three dollars goes to the same handful of tech-centric giants.

This isn't normal. At least, it hasn't been historically.

What's particularly fascinating (and potentially concerning) is how different things look overseas. The MSCI EAFE Index, which tracks developed markets outside North America, shows top-ten concentration of only about 15%. That's less than half the concentration we see in the U.S.

"The concentration levels we're seeing in American markets represent a fundamental shift in how capital is allocated," a portfolio manager at a major asset management firm told me last week. "It's not just about geography anymore—it's about market structure."

So what's behind this dramatic difference?

From my conversations with market strategists, two explanations emerge. First, there's the "winner-take-all" dynamic. American markets have become dominated by platform businesses with powerful network effects—companies like Google, Amazon, and Facebook that grow stronger with each new user. These businesses have characteristics that allow them to scale in ways traditional companies simply can't.

The second explanation is more cultural and structural. The American capital formation system—from venture capital to public markets—excels at identifying and rewarding transformational businesses. Europe and Japan have different corporate cultures, more fragmented markets, and regulatory environments that sometimes prioritize stability over explosive growth.

Look, neither approach is inherently superior. Concentration creates efficiency—resources flow to the most productive enterprises—but it also introduces vulnerabilities. When just a handful of companies drive market returns, one regulatory change or technological disruption can send shockwaves through entire portfolios.

Which brings us to the million-dollar question (or trillion-dollar, I suppose): Is this extreme concentration sustainable, or will we see a reversion to more historical norms?

History suggests these things are cyclical. Remember when energy companies dominated indices in the '80s? Or financial stocks before 2008? Those sectors eventually lost their outsized influence.

But... this time could be different. (I know, I know—dangerous words in investing.)

The unique characteristics of today's tech giants—their global reach, staggering profit margins, and quasi-monopolistic positions—suggest we might be in uncharted territory. These aren't companies that necessarily face the same competitive pressures or life cycles as industrial giants of the past.

Having followed markets through several cycles, I've learned to be skeptical of "new paradigm" claims. Yet the data can't be ignored.

For investors, this concentration disparity offers something more substantive to consider beyond valuation when weighing U.S. versus international exposure. If you believe in mean reversion, international markets—already less concentrated—might offer a structural advantage going forward.

Then again, international stocks have underperformed for so long that "value trap" warnings have become a cliché in investment circles.

Perhaps the wisest approach is viewing international exposure not just as geographic diversification but as structural diversification—a hedge against the potential risks of top-heavy markets.

In the meantime, we'll continue tracking market cap milestones with the enthusiasm of sports commentators. "And there goes Microsoft, crossing the $3 trillion line! What a performance, what a company!"

It would be funny if it weren't so important to our collective financial futures.