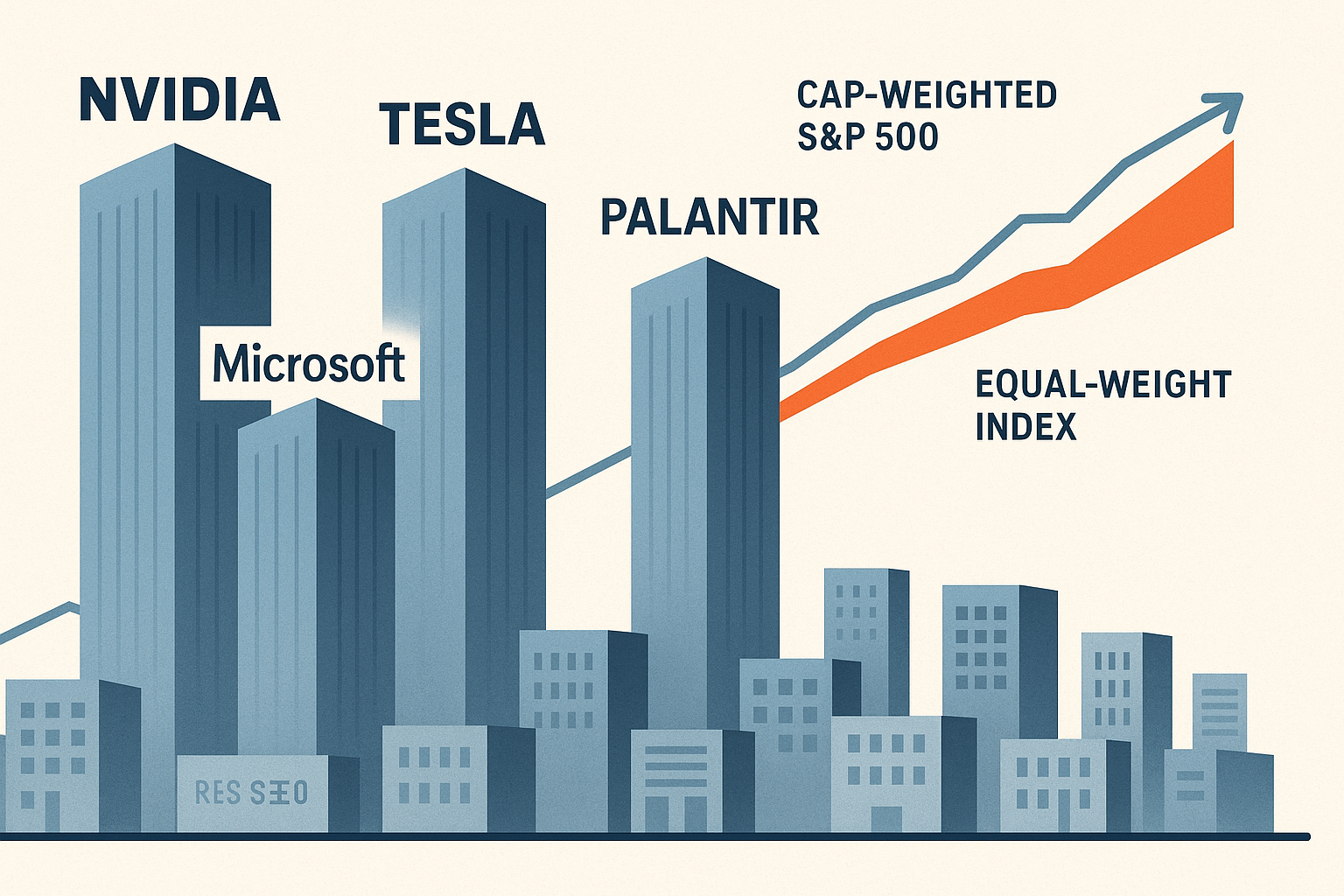

We're flirting with danger again, folks. That pesky ratio of the S&P 500 to its equal-weight counterpart is hovering around 20%—a level that's about as welcome on Wall Street as a tax auditor at a billionaire's birthday party.

I've been tracking this indicator for years, and let me tell you, it's got an eerie track record. Every single time we've approached this threshold in the past four decades, we've tumbled into recession territory soon after. It's like watching someone confidently stride toward a glass door for the fifth time, convinced that this time, they'll pass right through it.

The current market concentration isn't just high. It's stratospheric.

If the stock market were a neighborhood potluck, a handful of tech companies would have brought the main courses, desserts, and drinks, while everyone else showed up with those sad little plastic forks nobody ever uses.

"We're seeing a market that's increasingly dependent on fewer and fewer winners," a veteran fund manager told me last week over coffee (his third of the morning, suggesting he wasn't sleeping well). "That's not particularly healthy in the long run."

I think about this phenomenon through what I call the "elephant in the kiddie pool" theory. When massive stocks dominate an index, the water level looks higher for everyone—but most companies are actually struggling to keep their nostrils above water. The equal-weight index cuts through this illusion by giving Microsoft the same importance as some struggling regional bank you've never heard of. That's precisely why the growing gap between the two indices should keep you up at night.

Look at the usual suspects driving returns lately: NVIDIA, AMD, Tesla, alongside some AI newcomers like Palantir. These aren't just investments anymore—they're cultural phenomena, religious experiences, identities. When my Uber driver started explaining options strategies for Palantir (this actually happened Tuesday), I quietly moved some money to cash the next morning.

Now, concentration itself isn't inherently terrible. Innovation clusters. Winners emerge. Creative destruction and all that Schumpeterian jazz. But when a handful of companies dictate market returns to this degree, it creates brittleness in the system. One disappointing earnings call from Jensen Huang becomes everybody's problem. One antitrust action against Big Tech sends tremors through your retirement account.

Historically speaking, these concentration peaks always—and I mean always—coincide with periods of excessive optimism, where one sector becomes the answer to everything. In 2000, slap ".com" on anything and watch investors throw money at you. In 2007, financial engineering was supposedly going to eliminate risk forever (narrator: it didn't). Today? Just whisper "AI-powered" and venture capitalists start hyperventilating.

What fascinates me is how this concentration metric has proven to be a better recession predictor than many traditional indicators. While economists argue about yield curves and PMI data, this humble ratio has been quietly nailing it for decades. It's like the unassuming character in a detective novel who turns out to be the most observant one in the room.

The bulls, of course, have their counterarguments. "This time is different," they insist, because today's dominant companies generate actual profits (unlike in 2000) and have genuine competitive advantages. Maybe. I've covered enough market cycles to know that "this time is different" are often the four most expensive words in investing.

For everyday investors, this creates a genuine dilemma. Underweight the market leaders, and you've been trailing the benchmark for years. Pile in now? You might be buying at the peak. It's financial FOMO distilled to its essence.

The sensible approach isn't abandoning ship entirely but rather a gradual rotation. There are quality companies with reasonable valuations being completely overlooked in the AI gold rush. They're sitting there, accumulating dust while everyone crowds into the same handful of trades.

Meanwhile, keep that 20% threshold in mind. Markets have a wicked sense of humor about these psychological barriers. Just when everyone's convinced concentration can climb higher—that's precisely when mean reversion tends to make its dramatic entrance.

We're approaching what investment veterans call the "find out" phase of the "mess around" cycle. The only question is whether your portfolio will be ready when it arrives.