In what can only be described as an extraordinary legal confrontation, Federal Reserve Governor Lisa Cook has taken the unprecedented step of suing former President Donald Trump after he attempted to remove her from the central bank's Board of Governors. This isn't just another Washington dustup—it's a constitutional powder keg.

I've covered monetary policy for years, and I've never seen anything quite like this.

Cook, appointed by Biden back in 2022, isn't going quietly. Her lawsuit centers on the Federal Reserve Act's "for cause" provision—a legal standard that sets a high bar for removal, typically requiring something like serious misconduct rather than mere policy disagreements.

The timing couldn't be more fraught. Trump has repeatedly signaled he'd assert greater control over the Fed if returned to office, including his not-so-subtle hints about replacing Jerome Powell as chair.

What makes this whole mess so fascinating (and troubling) is how it exposes the strange institutional limbo the Fed has always occupied. The central bank exists in a peculiar governmental gray zone—created by Congress, led by presidential appointees, yet designed to function with independence from the political winds that blow through Washington every election cycle.

Mark Spindel, who literally wrote the book on Fed independence ("The Myth of Independence"), puts it bluntly: "The Federal Reserve's independence isn't explicitly written into the Constitution. It's more of a norm that evolved over decades."

A norm. Not a constitutional guarantee.

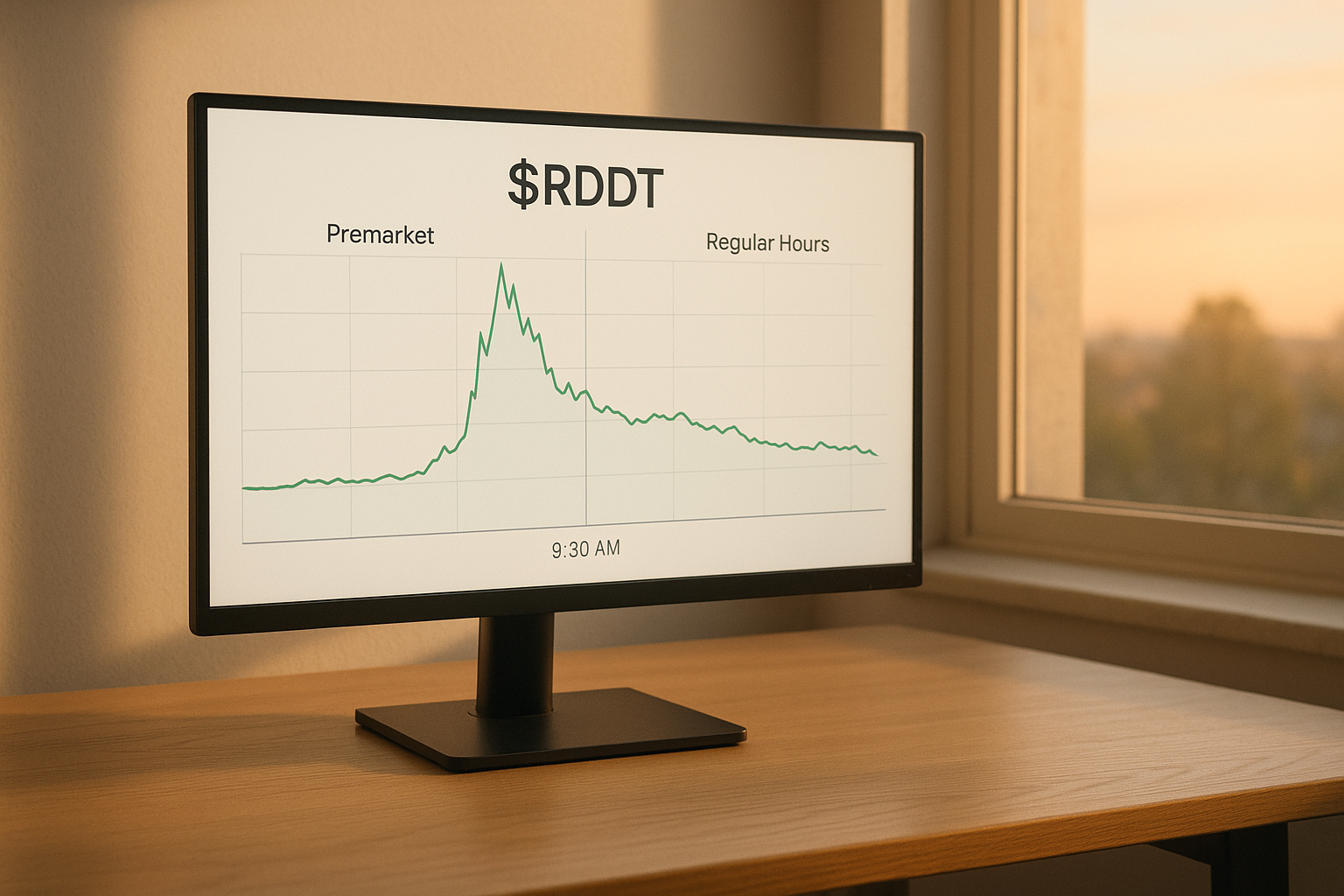

Markets, predictably, are getting jittery. Treasury yields jumped as traders started pricing in what you might call a "political interference premium." The dollar wobbled before finding its footing again.

Look, there's a rich historical irony here that shouldn't be missed. The Fed came into existence in 1913 partly as a response to financial panics, with its structure specifically designed to balance public accountability with insulation from short-term political pressures. Now, more than a century later, we're watching those same fundamental questions play out in federal court.

The lawsuit raises profound constitutional questions about presidential authority. While presidents clearly have the power to appoint Fed governors (with Senate confirmation, of course), their ability to fire them is much more limited—intentionally so.

What's particularly unnerving about this whole episode is how it lays bare the fragility of our institutional guardrails. Fed independence has largely been maintained through tradition and mutual restraint rather than ironclad legal protections. Presidents have always complained about Fed policy—sometimes loudly—but this kind of direct confrontation? That's terra incognita.

Former Fed officials are weighing in, and they're not mincing words. Ben Bernanke warned that "monetary policy conducted for short-term political gain rather than long-term economic stability rarely ends well." (That "rarely" is doing some heavy lifting there, wouldn't you say?)

The courts now face the delicate task of balancing executive power against the statutory independence granted to the Fed. Some legal experts I've spoken with think this could wind up before the Supreme Court given its constitutional significance.

For investors and, well, anyone who cares about economic stability, the stakes extend far beyond this particular legal spat. The Fed's credibility in fighting inflation and maintaining financial stability depends critically on its perceived independence from electoral pressures.

I remember interviewing a central banker years ago who told me, off the record, "Central bank independence is like oxygen—you only notice it when it's gone." That comment keeps ringing in my ears this week.

Whatever happens with Cook's lawsuit, one thing is clear: questions about central bank independence—once the domain of academic monetary economists and constitutional scholars—are suddenly front-page news. And in a financial system built entirely on confidence, that's... uncomfortable territory.

For markets that hate uncertainty more than bad news, the coming legal battle promises something they desperately try to avoid—months of unanswerable questions about the very foundation of our monetary system.