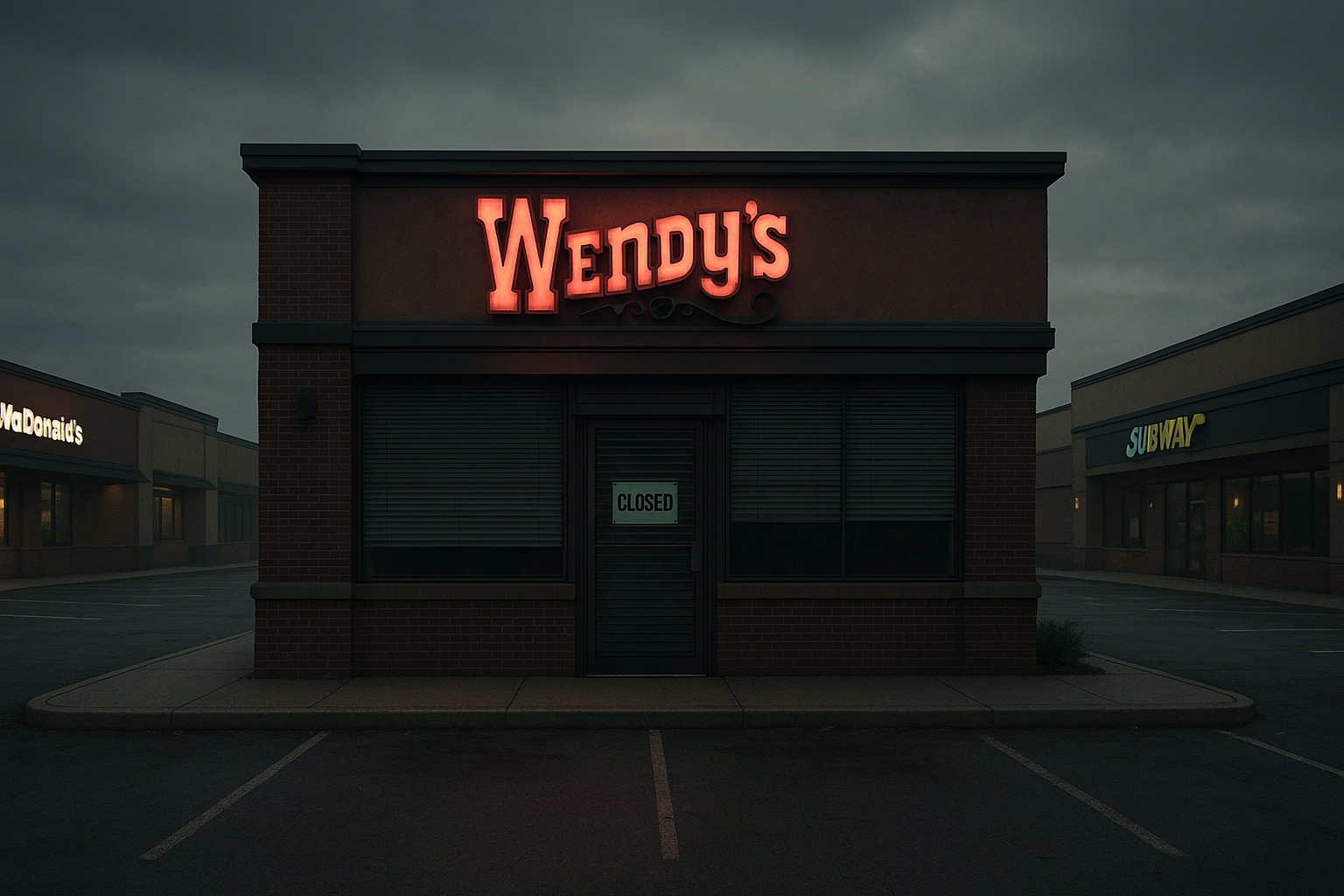

Wendy's is shuttering hundreds of locations across America, and let me tell you—this isn't just about fewer Frosty machines in suburban strip malls. It's the canary in the coal mine for an industry facing what might be its most significant restructuring since drive-thrus became standard.

I've been covering the restaurant industry for years, and something fundamental has shifted. Fast food joints are caught in what analysts are calling a "margin compression sandwich" (terrible pun intended). They're trapped between skyrocketing costs and customers who simply won't—or can't—pay the higher prices needed to cover them.

The math just doesn't work anymore.

Consider this: hourly wages in food service have jumped nearly 20% since pre-pandemic days. Ingredients cost more. Rent hasn't exactly gotten cheaper. Meanwhile, that value meal that used to cost $5? Good luck finding it now.

"We're operating on margins that make no mathematical sense," a Wendy's franchisee in the Midwest told me last week, requesting anonymity to speak frankly. "Corporate keeps pushing promotions that drive traffic but kill our bottom line. Something had to give."

What makes this particularly fascinating is how it exposes the growing tension in the franchise model itself. Most of these closing locations aren't corporate-owned but operated by franchisees who borrowed heavily to buy in. They're the ones feeling the squeeze first—and hardest.

Look, fast food has always been a volume business. Slim margins, high turnover. But the equation worked because costs were predictable. That's ancient history now.

And here's where it gets really interesting: consumers have options. Lots of them. When Wendy's raises prices 12% year-over-year (which they did), people don't just grumble and pay up. They delete the app and order from somewhere else.

Ghost kitchens. Fast casual chains. App-based delivery services with seemingly endless choices. The competitive landscape has exploded just as economics turned hostile.

McDonald's found this out the hard way when they rolled out—then quickly killed—their $5 meal deal earlier this year. The industry is discovering that price elasticity in fast food isn't what it used to be. Not even close.

There's a historical parallel worth noting. Remember the casual dining explosion of the late '90s? Chili's and Applebee's on every corner? That ended with a massive contraction once markets saturated. Fast food appears to be following the same playbook, just two decades later.

America simply has too many fast food restaurants—approximately 200,000 nationwide. That's roughly one for every 1,650 people. That density made sense when labor was cheap and competition limited. Those days are gone.

(Side note: the first Wendy's I ever visited as a kid in Ohio is among those closing. Nostalgia aside, I drove past last month and counted six other fast food options within two blocks. The market correction was inevitable.)

This doesn't mean the end of fast food. The strongest players—McDonald's, Chick-fil-A—will adapt and thrive in prime locations. But those third locations in markets that could really only support two? The underperforming stores in declining strip malls? They're going away.

Industry analysts I've spoken with expect several thousand more closures across chains in the next 36 months. Many franchisees are simply waiting for their agreements to expire.

"When your royalties are based on gross sales rather than profitability, and corporate keeps pushing discounts and deals, something's gotta break," another franchisee explained. "And it won't be corporate headquarters taking the hit."

The real story isn't about Wendy's specifically. It's about an industry that defined American eating habits for half a century now being forced to evolve or die.

Markets correct inefficiencies eventually. Even when they involve square hamburgers and chocolate Frostys.