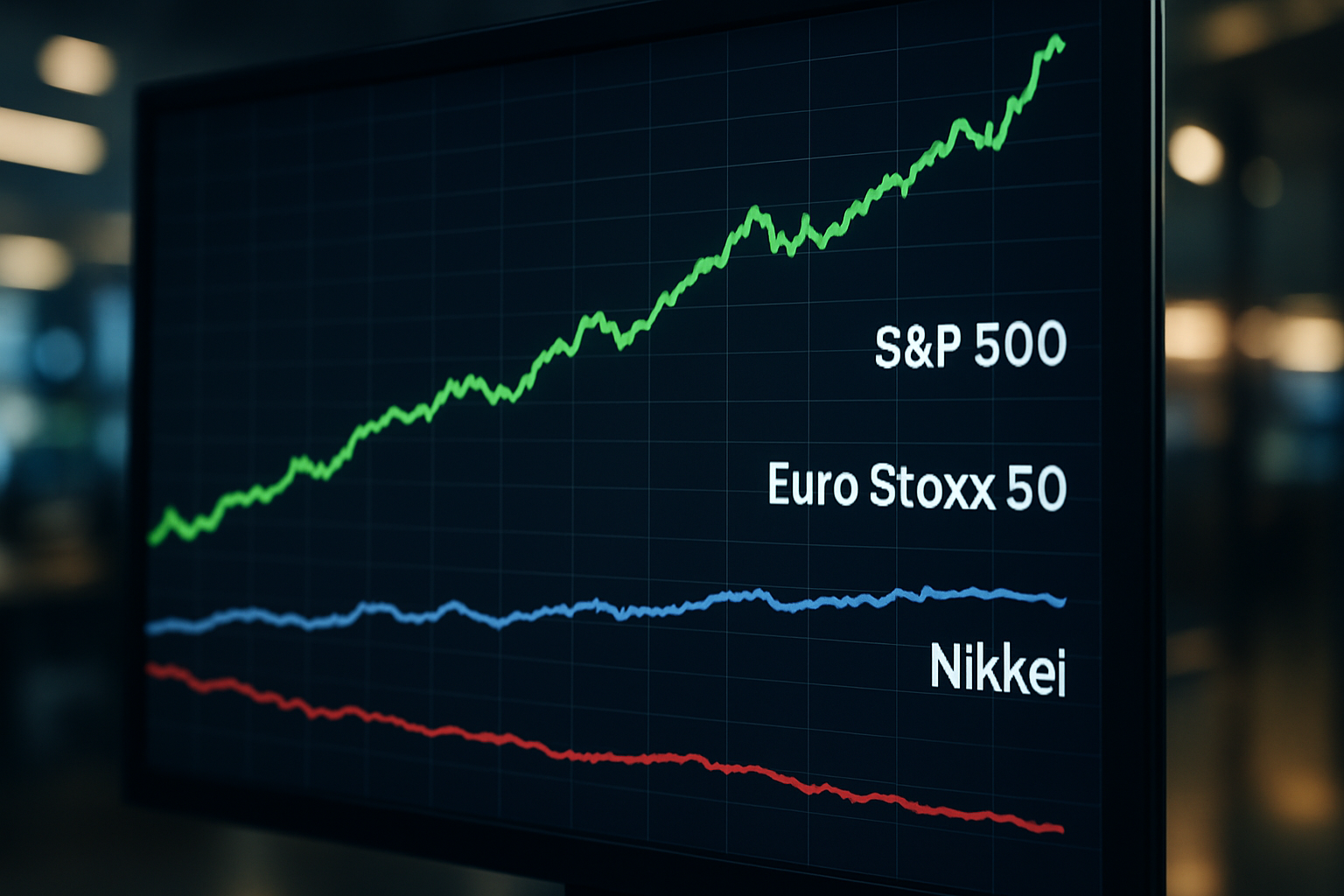

The American stock market just marked another quarter of outperformance against its developed-market peers, which at this point feels less like news and more like a regularly scheduled programming announcement. The S&P 500 is up 8.3% year-to-date while the Euro Stoxx 50 has managed a tepid 3.1% and Japan's Nikkei continues its roller-coaster relationship with corporate governance reforms, currently sitting at +4.2%.

I mean, we get it. American exceptionalism extends to equity markets. Moving on.

Except... not so fast. Behind these headline numbers lurks a more nuanced story about valuation divergences and structural shifts that might finally—finally!—be setting the stage for mean reversion. And if there's one thing markets eventually do (besides going up over very long time horizons), it's revert to means.

The Great Divergence: Stretched Beyond Reason?

The valuation gap between U.S. equities and their international developed market counterparts has reached levels that can only be described as, well, historically absurd. As of Q2 2025, the S&P 500 trades at a forward P/E of approximately 22.8x compared to 14.1x for the MSCI EAFE index. That's a 62% premium, folks. For context, the 20-year average premium has been closer to 25%.

A model that I often use when thinking about these divergences involves three key factors: growth differentials, sector composition, and investor psychology. Let's break it down:

Growth differentials: Yes, U.S. GDP growth continues to outpace European and Japanese economies (3.1% versus 1.8% and 1.2%, respectively). But the gap has actually narrowed from where it stood in 2021-2023. Yet the valuation premium has widened. Curious.

Sector composition: The standard explanation—"America has all the tech!"—held water for years. But European and Japanese markets have been quietly restructuring. The weight of technology and communication services in the MSCI EAFE has increased from 11% in 2020 to nearly 18% today. The composition differential explains perhaps a third of the valuation gap, not the whole enchilada.

Investor psychology: Here's where things get interesting. Capital flows suggest a self-reinforcing narrative loop where U.S. outperformance begets more investment, which begets more outperformance. It's a perfectly reasonable momentum strategy until, suddenly, it isn't.

Policy Divergence: The Central Bank Two-Step

The policy environment in 2025 presents another fascinating wrinkle. After the Fed's "higher-for-longer" stance finally cracked in late 2024 with the initiation of rate cuts, the ECB and Bank of Japan have followed different trajectories.

The ECB, ever fearful of inflation's ghost, has maintained relatively restrictive policy, while the BOJ has cautiously—very cautiously, like a man crossing a frozen lake in leather-soled shoes—begun normalizing after decades of ultra-accommodative measures.

This policy divergence creates what I'll call the "rotating haven effect." As each central bank pivots, capital sloshes around the global financial system seeking relative safety and yield. Currently, European fixed income looks increasingly attractive on a risk-adjusted basis compared to U.S. Treasuries, which could trigger a reallocation cascade that eventually reaches equity markets.

Look, I'm not saying European or Japanese stocks will suddenly trounce their American counterparts. Markets rarely work that cleanly. But the conditions for a multi-year reversion are accumulating like unpaid parking tickets on a diplomat's car.

Corporate Governance: The Quiet Revolution

Japan deserves special mention here. After decades of false starts, their corporate governance reforms are finally showing tangible results beyond mere share buyback announcements that evaporate upon closer inspection.

ROE for the Topix index has reached 9.8%—still below U.S. levels but representing a massive improvement from the 5-6% range that characterized most of the 2010s. Cross-shareholdings continue to unwind, and activist investors have moved from being treated as financial yakuza to reluctantly acknowledged participants in capital allocation discussions.

European markets, meanwhile, continue their long-running identity crisis. Are they value traps or value opportunities? The region's banking sector, long a performance anchor, has finally achieved respectable capital ratios and return metrics that don't make shareholders wince. The question remains whether this operational improvement can overcome the continent's structural growth limitations and political fragmentation.

The Small Matter of Artificial Intelligence

One cannot discuss international market divergences in 2025 without acknowledging the AI elephant in the room. The U.S. advantage in both developing and deploying AI technologies has been a significant driver of its market outperformance.

However, the second wave of AI implementation—what some are calling the "industrialization phase"—may actually benefit European and Japanese companies disproportionately. These economies' strengths in manufacturing, industrial automation, and process engineering align well with where AI applications are now focusing: operational efficiency rather than just pure technology development.

German mittelstand companies are quietly integrating AI into industrial processes with typical Teutonic thoroughness. Japanese robotics firms are embedding advanced AI capabilities into their systems. These developments rarely generate breathless headlines like "ChatGPT Creates Sonnet About Stock Market That Makes Warren Buffett Weep," but they're creating tangible productivity improvements.

The Investor Takeaway (or, What to Do With This Rambling Analysis)

If you've made it this far, you're probably wondering if there's an actionable investment thesis here beyond "maybe consider international stocks." There is, but it requires nuance.

The case for mean reversion in international developed markets relative to U.S. equities isn't primarily about macroeconomic superiority—America still maintains advantages in demographic trends, energy independence, and innovation ecosystems. Rather, it's about the mispricing of known factors and the potential for marginal improvement against dramatically lower expectations.

In other words, international developed markets don't need to become better than the U.S. to outperform; they just need to become better than the deeply pessimistic narrative embedded in their current valuations.

For investors with appropriate time horizons (measured in years, not quarters), a strategic reallocation toward quality companies in developed international markets—particularly those with improving corporate governance and tangible AI implementation strategies—represents a compelling risk-reward proposition.

Or maybe everything I've written is wrong, and U.S. exceptionalism will continue unabated until the S&P 500 comprises 99% of global market cap. Markets, after all, can remain irrational longer than you can remain solvent—or patient.

Either way, the divergence between U.S. and international developed markets represents one of the most interesting macro setups in global equities right now. And in a market environment where genuine inefficiencies are increasingly scarce, that alone deserves attention.